SEARCH

Alton Brown’s Thanksgiving Turkey Survival Guide: everything you’ve ever wanted to know about the bird.

It’s the month of Thanksgiving and all across the land, people are freaking out because they’re panicked about various aspects of their Thanksgiving meal, most notably, that darned turkey.

Here in the test kitchen, we’re here to put an end to that panic by arming you with confidence in the form of knowledge: What to look for when shopping, how to brine the bird, and recipes for the perfect roast turkey.

So, without further ado, dig into our Thanksgiving Turkey Survival Guide:

CHOOSING A TURKEY

When it comes to procuring the bird, you have three main choices, though you may not know it and your megamart may not tell you. In our view, these three categories are traditional, aka broad-breasted whites; specialty, a catchall category that includes marketing terms like “natural,” “free-range,” and “heirloom;” and heritage breeds.

At the end of the day, the best way to procure a top-quality bird is to chat with your poultry-person, aka your local butcher.

To make sense of all the chatter, we’ve compiled a handy (but by no means comprehensive) guide to turkey terminology:

Traditional

Broad-breasted whites, developed in the 1960s to satisfy the average American’s love of white meat, account for 99.99 percent of megamart turkeys. These birds are so heavy and large-breasted that they cannot fly or mate naturally. They grow to between 16 and 22 pounds in 12 to 14 weeks, after which point, they are processed. After processing, they weigh between 12 and 18 pounds. On average, they cost about $1.50 per pound, making them the most affordable Thanksgiving bird.

Specialty

Natural: This label does not refer to how the turkey was raised, but rather how it was processed. Basically, it means no artificial ingredients or color have been added to the bird, and that it has been minimally processed. Natural birds tend to be drier, which can be remedied with brining. Natural poultry can be given antibiotics.

Kosher: These birds are broad-breasted whites processed under rabbinical supervision. They are grain-fed, have access to the outdoors, are given no antibiotics, and are soaked in salt brine. Salting seasons the meat, improves texture, and retains moisture. However, purchasing a kosher bird means you cannot control its salt level. You will also definitely want to skip an at-home brine.

Organic: An organic label indicates that the turkey has been certified by the USDA to have been raised on 100 percent organic feed, have year-round access to the outdoors, and given zero antibiotics or growth hormones.

Self-Basting: These birds are injected with or marinated in a solution. Such a treatment increases the moisture content for a juicer bird, but it can mask the turkey’s flavor. Just as with kosher birds, you will not be able to control the salt level of your turkey, and you absolutely, 100 percent do not want to brine a self-basting bird.

Free-Range: These birds have access to the outdoors, but they don’t necessarily have room to roam. Free-range is commonly misunderstood to mean the same thing as “organic” or “naturally processed;” however, this label does not refer to the birds’ feed or handling.

No Hormones Added: This statement is sometimes added to labeling; however, it is meaningless since a USDA regulation prohibits growth hormones in U.S. poultry and eggs.

Heritage Breeds

These are turkeys bred from old-fashioned (aka heirloom) breeds and are more closely related to wild turkeys than conventional birds. The American Poultry Association’s (APA) Standards of Perfection recognizes eight heirloom turkey breeds: Black, Bronze, Narragansett, White Holland, Slate, Bourbon Red, Beltsville Small White, and Royal Palm. You may see other breeds, like Jersey Buff and White Midget, show up at butcher shops; but these have yet to be recognized by the APA.

All heritage birds must meet the following criteria:

– Natural mating and growth

– Long, productive outdoor lifestyle

– A slow growth rate of 7 to 8 months, which is two times longer than commercial turkeys

Because of this slower growth rate, heritage birds have time to develop an extra layer of fat, which is said to add to their deeper flavor. And because they are allowed to run and fly, their meat is firmer, chewier, and darker without being gamey.

Since there is a limited supply of heritage birds each year, they are a lot more expensive than commercial varieties, usually clocking in at $7 to $10 per pound.

SHOPPING TIPS

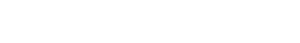

First of all, make sure you know what size bird you’re looking for before heading to the megamart. Here’s a handy chart to help you figure it out:

If you’re doing your shopping far enough in advance, there’s nothing wrong with purchasing a frozen turkey; however, it is important to note that many frozen birds contain up to an 8 percent salt solution that acts both as a preservative and adds to the final weight. Ask your butcher for a deep-chilled or refrigerated turkey (a bird that’s been stored between 0 and 26°F), if possible.

Oh, and if you opt for a fresh bird (a turkey that has never been stored below 26°F), just make sure you have room in your fridge BEFORE you head to the store.

A few additional things to consider when shopping:

- Look for a bird with packaging that’s damage free, isn’t sticky, and is free of any “off” aroma.

- If you can see the turkey, look for plump breasts with moist pinkish-white skin, and no blemishes, bruises, or weird smells.

- Size:

-

- A smaller bird (12 to 14 pounds) fits better in the fridge.

- A larger (18-plus pound) bird increases the likelihood that the turkey will be overcooked. Basically, because giant birds are almost entirely breast meat, you end up with this huge amount of white meat on top of the turkey that insulates the dark meat. This means that it takes longer to cook the dark meat through and, thus, overcooks the breasts. If you insist on cooking a giant bird, you should definitely brine.

- If you’re feeding a crowd, consider roasting two birds in the 12-pound range rather than one huge bird. Or, you could mix it up by throwing the second turkey on the grill or in the smoker.

STORAGE

- Store fresh birds on ice or in the fridge for up to four days.

- Frozen birds can be kept in the freezer for up to six months.

THAWING

We have two non-negotiables when it comes to thawing your Thanksgiving turkey:

- DO NOT defrost at room temperature.

- DO NOT cook partially frozen poultry.

If you do find yourself with a partially frozen bird the week of, we do have a small work around: You can, in fact, brine a still-frozen bird. Simply fill a large cooler with a brine made with ice water (more on that below), submerge the critter, cover, and stow away in a cool place, like a closet or garage. By the time the bird is finished with its two-day brine, it’s thawed and ready to roast.

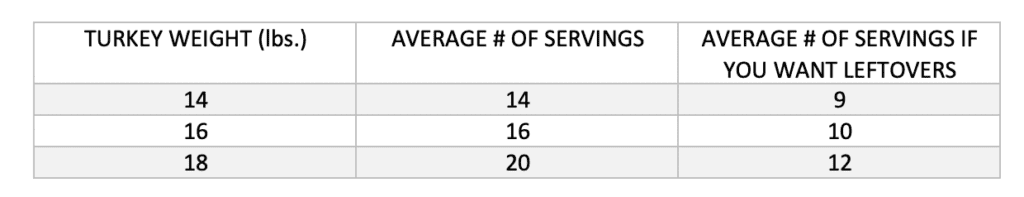

To avoid disaster, plan ahead: Make space in your fridge and figure out how long it will take for your turkey to thaw:

BRINING

The Good Eats faithful know that we’re big fans of brining. Why, you ask?

One of the best ways to ensure a moist bird is to brine, which basically means to treat with or steep in a strong solution of water, salt, and, sometimes, a sweetener like brown sugar or honey — while the sweetener may or may not permeate the meat in any substantial way, it does help with Maillard reactions on the surface of the bird…aka, nice, even browning.

The more important part of the equation is the salt solution. This mixture drains the moisture out of the poultry, creating a flavorful brine, which is then reabsorbed into the meat without adding additional water and diluting the flavor.

Why bother? Well, salt has two important effects on the meat:

- It dissolves the protein in the muscle, ensuring a more tender turkey.

- Salt and protein reduce moisture loss during cooking; in fact, brined meat can lose up to 75 percent less water than a non-brined bird.

Bonus: The salt enhances the turkey’s natural flavors.

If crispy skin is your end goal, try a dry brine. By rubbing the bird inside and out with salt and ground spices, and letting it sit on a wire rack-lined baking sheet — uncovered — in the fridge for a few days, you get an equally flavorful result without messing with the soak. The only downside: You have to find room in your fridge.

In short, taking the time to properly brine your bird is worth it in both flavor and texture of the final product. You know what we always say about patience…

RECIPES

Ready to put your newfound knowledge to the test? Here are a few tried and true turkey applications to get you started:

- Good Eats Roast Turkey

- Spatchcocked Roast Turkey

- Deep-Fried Turkey

- Honey Brined Smoked Turkey

- Turkey with Stuffing

- Turketta

As for those Thanksgiving leftovers, you can’t go wrong with classic Turkey Salad.

And don’t skimp on the sides…

- All-Corn Cornbread

- Just Cranberry Sauce

- Green Bean Casserole 2.0

- Bacon Maple Sprouts

- Make-Ahead Thanksgiving Gravy

- Leeked Whipped Potatoes

- Brown and Serve Dinner Rolls

- Pumpkin Cheesecake

Happy Thanksgiving!